Research Article / Open Access

DOI: 10.31488/jjm.1000126

Knowledge on Under-Five Childhood Immunization Schedule amongst Parents at Nurseries in Putrajayaand Cyberjaya in Malaysia

Nor AfiahMohd Zulkefli1, Mohammad Farhan Bin Rusli1, Muhammad Hanafiah Juni1

Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

*Corresponding author:Dr.Mohammad Farhan Bin Rusli, Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Abstract

Background: Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization has been identified as a key factor in determining understanding and compliance to the schedule. Understanding the current levels of knowledge and introducing a health intervention to improve the level will benefit the population to be healthier and reduce morbidity. Methods: A quasi-experimental study was conducted in nurseries in Putrajaya and Cyberjaya from January 2016 to January 2018. 98 respondents from Putrajaya were the intervention group and 98 from Cyberjaya were the wait-listed control group. The intervention was a technology based health education module. Intervention groups received the intervention through the messaging service of Whatsapp at pre-determined intervals. Respondents answered a validated, self-administered questionnaire at baseline, immediately post-intervention and 3 months post-intervention that were specifically targeted to examine their levels of knowledge.Results: Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Version 23. The level of knowledge at baseline was 58.9% for the intervention group and 61.7% for the control group with no significant difference between both groups. At 3 months post-intervention the intervention group was 95.5% and the control was at 85.1%. Immediate post intervention showed a big gap between both groups.Conclusion: The level of knowledge improved after receiving the health intervention module and was effective in the increasing of knowledge among the respondents. However, there are still gaps in research that must be addressed in future studies to help further improve knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule.

Keywords: under-five childhood immunization schedule, adherence, knowledge on under-five childhood immunization, level of knowledge

Introduction

Immunization is the process to replace a predicted natural primary contact between the human body and a hostile organism with a much safer artificial contact, in order to allow the build up of antibodies that increase the immunity with subsequent natural contact. The World Health Organization defines immunization as a process where a person through a vaccine administration obtains immunity [1]. The information and knowledge on vaccines is important as it allows the parents to understand the entire purpose of the childhood immunization program.

Knowledge has been identified as a factor by various studies that are discussed below and plays a key component on the understanding of under-five childhood immunization schedule. The level of knowledge varies in contrast with the regions as those from more developed countries showed levels of knowledge at 80% or more while those from developing countries at less than 70% [1].A Malaysian study demonstrated that knowledge was critical in the understanding of childhood immunization schedule [2]. Not only this but knowledge on age of vaccination showed those who knew the age were three times more likely to adhere to the schedule [3] and those who had further knowledge on the completion of the vaccine age were four times more likely to comply. Furthermore knowledge on the EPI schedule resulted in three times more likely compliance to the childhood immunization schedule [4]. The knowledge on vaccines plays a pivotal role in the ability of the parent to comprehend the importance of adhering to the childhood immunization schedule. As a study showed those with lack of knowledge on vaccines were six times more likely to fail to comply with the schedule [5]. Those who had knowledge that vaccines could prevent disease and also limit illness to the child were more likely to adhere to the schedule [6].

Knowledge regarding childhood immunization schedule, its vaccines, its effects and the diseases that may be prevented is important in allowing the parents to make informed and sound decisions in regards to immunizing the child and this study allows for the measuring of the knowledge in the population.Improvement in knowledge on the timeliness of vaccines also enables the child to receive the required immunizations according to the set schedule that may improve the development through the proper antibody build up in the body.

Methodology

Recruitment

Recruitment was initiated by approaching all the nurseries listed under the welfare department in both areas. Those that were showed interest and were willing to join the study were then asked to provide the list of all parents and children who were registered in the nurseries. As this was a quasi-experimental study, the researcher chose Putrajaya to be the intervention group and Cyberjaya to be the control group. The list was then analyzed and the data gathered was crosschecked to determine if the inclusion and exclusion criteria were fulfilled. All those short-listed were contacted directly to ask for consent to involve them in the study. Those who refused were excluded and this resulted in the recruitment of 196 respondents in total, 98 in the intervention group and 98 for the control group. The participants were then provided with the information that they would now be included in a Whatsapp® chat group and that further instructions will be provided once the group is initiated.

Participants

Men and women are eligible to participate in the study if they were Malaysian, had a child under 24 months old who had an immunization appointment in 3 months, there were non-adherent to the immunization schedule and if they had more than one child registered in the nursery, the youngest child will be selected. To ensure commitment to the research group, the respondents were allowed to have access to a medical officer from 8am to 10pm daily for any questions pertaining to general health that would be answered as quickly as possible.

Setting

The research utilized the chat group and was active daily from 8am to 10pm daily for 3 consecutive months. At the start of the intervention, the participants were given a thorough explanation regarding the rules of communication, what type of materials they are to expect and not to spread or share the information to other friends and family until the end of the study period. Respondents were also told that none of their information will be further recorded where no names needed to be given or introductions among respondents to be necessary. The module was given in a systematic timeline where the respondents would receive information on Mondays, Wednesday, Fridays and Sundays between 8am and 8.30am. The moderator of the group was a trained medical officer well versed in the under-five childhood immunization schedule.

Measurement instruments

The outcome of the research was to observe the knowledge of the respondents on the under-five childhood immunization schedule at three varying time points. The first at baseline, the second immediately post intervention and the third at 3 months post intervention. The respondents were given a tested and validated self-administered questionnaire that comprised of 20 questions on knowledge. There were 3 options given with answers of Yes, No and I don’t know. A mark was given for each correct response and no marks given for incorrect and I don’t know responses. There were no negative or reverse questions posted in the questionnaire. The final marks were than calculated over a percentage with the lowest attainable score of 0% and the highest 100%.

Analysis

Data was first analyzed descriptively to identify means of the response. Log transformation was performed to reduce skewness and to obtain normal distribution of data, and outliers were then removed by checking the Mahalanobis Difference. For knowledge, One-way ANOVA was utilized to measure between groups and GLM Repeated Measures were used to measure within groups, and bivariate analysis of which independent t-test was used for categorical factors and Pearson’s correlation for continuous factors to measure association to measure the association of factors.

Results

A total of 60 nurseries in Putrajaya and 12 in Cyberjaya were identified. However only 16 nurseries agreed to participate from Putrajaya and 7 from Cyberjaya. These administrators proceeded with sending the immunization records of those registered under their care with a total of 467 immunization cards from Putrajaya and 237 from Cyberjaya being screened for eligibility. The total number of non-adherence obtained from the screening and fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were 250 for Putrajaya and 151 for Cyberjaya. The final respondents were then selected utilizing simple random sampling using Microsoft Excel spread sheet and formulating the random generator whereby 98 participants were in the intervention group (Putrajaya) and the control group (Cyberjaya). The intervention group was then collected into a Whatsapp® Chat Group where the Health Education Module is presented on a systematic and timely basis. The control group consequently is wait-listed until the end of the intervention process. This resulted in a response rate of 113%. However at the end of the study, the intervention group had 84 respondents and the control group had 80 respondents. This meant that the drop out rate was 16%. Figure 1 below shows the flowchart of the respondent recruitment and drop-outs.

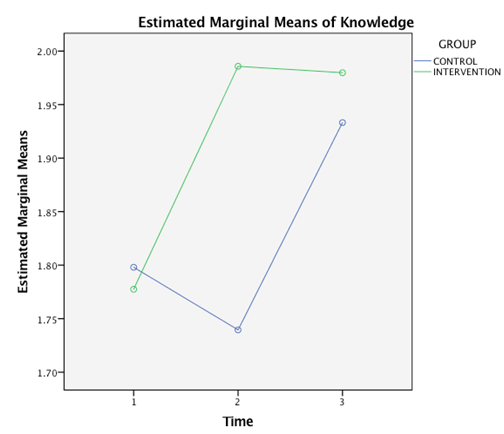

Figure 1.Profile plot of knowledge means for intervention group and control group against the different time points.

The Table 1 shows the scoring obtained by the respondents to each of the questions in the section. Most of the respondents (85.2%) provided the correct answer to the question “It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child” and 83.7% of them also gave the correct response to “There are many different type of vaccines”. However 54.1% respondents gave an incorrect answer to “Some skin reactions are normal after vaccinations”.

The immediate post intervention knowledge scores are shown in Table 2 below. It shows that the highest correct answer (89.2%) was to the statement “It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child” and the most incorrect answer was to the statement “Some skin reactions after vaccination is normal” with 37.5% respondents giving wrong answers.

The transformed log showed knowledge means of 58.9% ± 1.09 at baseline, increased to 97.7% (1.02) at post intervention and reduced to 95.5% ± 1.02 at 3 months post intervention for the intervention group. Using an ANOVA with repeated measures showed Mauchly’s test of sphericity to be significant (p<0.001) thus with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction, the mean scores for knowledge were statistically significantly different for the intervention group (F (1.014, 84.191) = 25.414, p<0.001). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that there was a significant mean difference between baseline and immediate post intervention (p<0.001), and also between baseline and 3 months post intervention (p<0.001). However between immediate post intervention and 3 months post intervention there was no significant difference (p=0.410). As for the control group, transformed log data of knowledge resulted in means of 61.7% ± 1.05 at baseline, reducing to 54.9% ± 1.09 immediate post intervention and increased to 85.1% ± 1.02 at 3 months post intervention. The repeated measures ANOVA showed the Mauchly’s test of sphericity to be significant at (p<0.001) resulting in the Greenhouse-Geisser correction to show mean scores for the control group were statistically significantly different (F (1.368, 108.096) = 14.879, p<0.001). Adjustment for multiple comparison utilized Bonferroni for post hoc tests showed no significant difference between baseline and immediate post intervention knowledge scores for the control group (p=0.584) although between baseline and 3 months post intervention to be significant (p<0.001). Immediate post intervention also showed a significant difference (p<0.001) when compared to 3 months post intervention knowledge scores within the control group. Between subject effects showed a significant difference (p<0.001), thus we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is a significant difference on the knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule at baseline, immediate post intervention and 3 months post intervention within and between intervention group and control group. The profile plots shows that at baseline the control group reduced its marginal mean when approaching the second time point and increased at 3 months post intervention. As for the intervention group there is a sharp increase from baseline to immediate post intervention and a slight decline at 3 months post intervention.

One-way ANOVA showed the comparison between the intervention group and control group at the different time points. At baseline, there was statistically no significant difference between the intervention group and control group mean knowledge (p=0.651), however there was significant difference at immediate post intervention (p<0.001) and also at 3 months post intervention (p<0.001).

To measure association between the factors and knowledge, the Pearson’s correlation was used to measure between two continuous variables and independent t-test for covariates that were categorical. The tables presented below are compiled to show all analysis done with Pearson’s correlation in one table, and the Independent T-Test in another table. This was done with all covariates in comparison to baseline knowledge. For the test using the Pearson’s correlation, none of the factors were found to be significant. The bivariate analysis using Independent T-Test showed significant factors were education (p=0.011), clinic follow up ((p<0.001), follow up during pregnancy (p=0.003), ATT vaccine (p=0.032), make decision (p=0.009), understanding on vaccines (p<0.001) and consult husband (p=0.003).

Table 1. Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule at baseline.

| Knowledge Questions | CORRECT | INCORRECT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child | 167 | 85.2 | 29 | 14.8 |

| My child will complete all vaccinations by 18 months old | 151 | 77.0 | 45 | 23.0 |

| The immunization schedule dates must be followed | 156 | 79.6 | 40 | 20.4 |

| Polio is a disease that can be prevented by taking vaccine | 119 | 60.7 | 77 | 39.3 |

| Hepatitis B immunization requires 3 doses | 93 | 47.4 | 103 | 52.6 |

| Immunization prevents my child from getting sick | 134 | 68.4 | 62 | 31.6 |

| Information on vaccine can be obtained from the internet | 112 | 57.1 | 84 | 42.9 |

| The Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine is a combination of three vaccines | 107 | 54.6 | 89 | 45.4 |

| My child needs to get the vaccination as close to the date given as possible | 143 | 73.0 | 53 | 27.0 |

| The first vaccine my child has receive is the BCG vaccine | 144 | 73.5 | 52 | 26.5 |

| Many diseases can be prevented by taking vaccines | 142 | 72.4 | 54 | 27.6 |

| All vaccinations must be recorded in my child immunization book | 156 | 79.6 | 40 | 20.4 |

| The immunization book must be kept safe | 149 | 76.0 | 47 | 24.0 |

| My child can harm others if I don’t complete the vaccination | 100 | 51.0 | 96 | 49.0 |

| Some skin reactions after vaccination is normal | 90 | 45.9 | 106 | 54.1 |

| My child can be severely ill if they don’t receive vaccination | 100 | 51.0 | 96 | 49.0 |

| Vaccination is a very quick procedure | 149 | 76.0 | 47 | 24.0 |

| I can get my child vaccinated even in private clinics | 147 | 75.0 | 49 | 25.0 |

| There are many different types of vaccines | 164 | 83.7 | 32 | 16.3 |

| My local health clinic can provide me with all the information I need in regards to childhood immunization. | 163 | 83.2 | 33 | 16.8 |

Table 2. Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule at immediate post intervention.

| Knowledge Questions | CORRECT | INCORRECT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child | 157 | 89.2 | 19 | 10.8 |

| My child will complete all vaccinations by 18 months old | 134 | 76.1 | 42 | 23.9 |

| The immunization schedule dates must be followed | 151 | 85.8 | 25 | 14.2 |

| Polio is a disease that can be prevented by taking vaccine | 144 | 81.8 | 32 | 18.2 |

| Hepatitis B immunization requires 3 doses | 133 | 75.6 | 43 | 24.4 |

| Immunization prevents my child from getting sick | 138 | 78.4 | 38 | 21.6 |

| Information on vaccine can be obtained from the internet | 132 | 75.0 | 44 | 25.0 |

| The Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine is a combination of three vaccines | 126 | 71.6 | 50 | 28.4 |

| My child needs to get the vaccination as close to the date given as possible | 150 | 85.2 | 26 | 14.8 |

| The first vaccine my child has receive is the BCG vaccine | 146 | 83.0 | 30 | 17.0 |

| Many diseases can be prevented by taking vaccines | 146 | 83.0 | 30 | 17.0 |

| All vaccinations must be recorded in my child immunization book | 153 | 86.9 | 23 | 13.1 |

| The immunization book must be kept safe | 150 | 85.2 | 26 | 14.8 |

| My child can harm others if I don’t complete the vaccination | 131 | 74.4 | 45 | 25.6 |

| Some skin reactions after vaccination is normal | 110 | 62.5 | 66 | 37.5 |

| My child can be severely ill if they don’t receive vaccination | 120 | 68.2 | 56 | 31.8 |

| Vaccination is a very quick procedure | 147 | 83.5 | 29 | 16.5 |

| I can get my child vaccinated even in private clinics | 157 | 89.2 | 19 | 10.8 |

| There are many different types of vaccines | 158 | 89.8 | 18 | 10.2 |

| My local health clinic can provide me with all the information I need in regards to childhood immunization. | 156 | 88.6 | 20 | 11.4 |

Table 3. Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule at 3 months post intervention.

| Knowledge Questions | CORRECT | INCORRECT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child | 163 | 99.4 | 1 | 0.5 |

| My child will complete all vaccinations by 18 months old | 154 | 93.9 | 10 | 6.1 |

| The immunization schedule dates must be followed | 147 | 89.6 | 17 | 10.4 |

| Polio is a disease that can be prevented by taking vaccine | 145 | 88.4 | 19 | 11.6 |

| Hepatitis B immunization requires 3 doses | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| Immunization prevents my child from getting sick | 140 | 85.4 | 24 | 14.6 |

| Information on vaccine can be obtained from the internet | 147 | 89.6 | 17 | 10.4 |

| The Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine is a combination of three vaccines | 143 | 87.2 | 21 | 12.8 |

| My child needs to get the vaccination as close to the date given as possible | 138 | 84.1 | 26 | 15.9 |

| The first vaccine my child has receive is the BCG vaccine | 149 | 90.9 | 15 | 9.1 |

| Many diseases can be prevented by taking vaccines | 146 | 89.0 | 18 | 11.0 |

| All vaccinations must be recorded in my child immunization book | 148 | 90.2 | 16 | 9.8 |

| The immunization book must be kept safe | 146 | 89.0 | 18 | 11.0 |

| My child can harm others if I don’t complete the vaccination | 147 | 89.6 | 17 | 10.4 |

| Some skin reactions after vaccination is normal | 152 | 92.7 | 12 | 7.3 |

| My child can be severely ill if they don’t receive vaccination | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| Vaccination is a very quick procedure | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| I can get my child vaccinated even in private clinics | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| There are many different types of vaccines | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| My local health clinic can provide me with all the information I need in regards to childhood immunization. | 155 | 94.5 | 9 | 5.5 |

Table 4. Knowledge within intervention group and control group

| Time | Mean ± SD (log) | 95% CI (log) | Geometric Mean ± SD | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| Intervention | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.77 ±0.04 | 1.70 | 1.86 | 58.9 ±1.09 | 50.12 | 72.44 |

| Immediate | 1.99 ±0.01 | 1.98 | 1.99 | 97.7 ±1.02 | 95.50 | 97.72 |

| 3 months | 1.98 ±0.01 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 95.5 ±1.02 | 91.20 | 97.72 |

| Control | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.79 ±0.02 | 1.77 | 1.84 | 61.7 ±1.05 | 58.88 | 69.18 |

| Immediate | 1.74 ±0.04 | 1.67 | 1.82 | 54.9 ±1.09 | 46.77 | 66.06 |

| 3 months | 1.93 ±0.01 | 1.92 | 1.95 | 85.1 ±1.02 | 83.18 | 89.13 |

Table 5. Group comparison between intervention group and control group at different time points for knowledge.

| Time | df | Mean square (log) | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 | 0.017 | 0.205 | 0.651 |

| Immediate | 1 | 2.485 | 44.343 | <0.001 |

| 3 months | 1 | 0.089 | 31.259 | <0.001 |

Table 6. Factors associated with knowledge at baseline.

| Variable | N | r | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 164 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Number of children | 164 | -0.006 | 0.936 |

| Children living in the same household | 164 | 0.014 | 0.862 |

| Child sibling number | 164 | 0.001 | 0.998 |

| Age during delivery | 164 | -0.029 | 0.712 |

Table 7. Factors associated with knowledge at baseline

| Variable | Mean Difference (log) | 95% CI (log) | Geometric Mean Difference | 95% CI | t | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Ethnicity | -0.11 | -0.39 | 0.19 | 6.76 | 3.07 | 14.49 | -0.710 | 0.479 | ||

| Education | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 12.49 | 9.72 | 15.98 | 2.571 | 0.011 | ||

| Occupation | -0.10 | -0.31 | 0.11 | 6.94 | 3.90 | 11.88 | -0.965 | 0.336 | ||

| Income | -0.02 | -0.12 | 0.08 | 8.55 | 6.59 | 11.02 | -0.400 | 0.690 | ||

| Smoking | 0.14 | -0.43 | 0.71 | 12.80 | 2.72 | 50.29 | 0.491 | 0.624 | ||

| Religion | -0.10 | -0.39 | 0.19 | 6.94 | 3.07 | 14.49 | -0.710 | 0.479 | ||

| Living with parents | -0.01 | -0.23 | 0.21 | 8.77 | 4.89 | 15.22 | -0.68 | 0.946 | ||

| Living with in laws | -0.06 | -0.22 | 0.09 | 7.71 | 5.03 | 11.30 | -0.815 | 0.416 | ||

| Residence | 0.14 | -0.12 | 0.40 | 12.80 | 6.59 | 24.12 | 1.045 | 0.298 | ||

| Child living with mother | -0.14 | -0.72 | 0.43 | 6.24 | .91 | 25.92 | -0.491 | 0.624 | ||

| Clinic f/up | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 18.05 | 13.45 | 24.70 | 4.500 | <0.001 | ||

| Sibling was hospitalized | -0.44 | -0.20 | 0.11 | 2.63 | 5.31 | 11.88 | -0.563 | 0.574 | ||

| Follow up pregnancy | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 23.55 | 12.80 | 42.65 | 3.028 | 0.003 | ||

| Postnatal follow up | 0.02 | -0.27 | 0.31 | 9.47 | 4.37 | 19.42 | 0.135 | 0.892 | ||

| ATT vac. | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 15.22 | 9.47 | 24.70 | 2.165 | 0.032 | ||

| BCG vac. | 0.07 | -0.34 | 0.48 | 10.75 | 3.57 | 29.20 | 0.313 | 0.754 | ||

| Make decisions | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 12.18 | 9.72 | 15.22 | 2.628 | 0.009 | ||

| Understand vaccines | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 15.22 | 11.59 | 19.42 | 3.938 | <0.001 | ||

| Consult husband | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 13.13 | 10.22 | 16.38 | 3.036 | 0.003 | ||

| Public transport | 0.08 | -0.05 | 0.20 | 11.02 | 7.91 | 14.85 | 1.248 | 0.214 | ||

| Distance to clinic | 0.02 | -0.09 | 0.13 | 9.47 | 7.13 | 12.49 | 0.296 | 0.768 | ||

| *Significant at p< 0.05 | ||||||||||

Discussion

Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule was measured at three different time points. At baseline, the most wrong answer provided was to the statement “Some skin reactions are normal after vaccinations”. This then dropped to 37.5% immediate post-intervention and reduced even further to 7.3% 3 months post intervention. The highest correct response (85.2%) was to the statement “It is important to know the vaccinations needed for my child”. This increased to 89.2% immediate post intervention and further to 99.4% 3 months post intervention.Knowledge on under-five childhood immunization schedule is expected to increase in the intervention group as the technology based health intervention module provided sufficient, repetitive and informative knowledge with simple to understand language and visualizations to the intervention group. With receiving intervention there may be an increase in self-understanding and increase concern regarding health that effects the knowledge of the intervention group [7]. As seen in the results where the parameter of time is reported, the percentage of good knowledge of the entire group actually decreases by 45% at immediate post-intervention and then further to 48% at 3 months post intervention. This occurred because the sampling was inclusive of both the intervention and control group and demonstrates the severe reduction in overall knowledge contributed by the control group. A study concluded that those with knowledge on immunization or received information regarding the childhood immunization were more likely to have better knowledge and understanding [3]. The intervention group were measured at three time points. At baseline the intervention group showed a mean of 58.9%, at one month 97.7% and at three months post-intervention 95.5%. The change in mean score between baseline and one-month post intervention is expected as they had received the technology based health intervention module. As for the change between one-month and three months post intervention, where a slight drop in mean percentage scores is noted, this decrease may be due to the complacency of time where prolong periods of intervention causes respondent to lose interest [8]. Furthermore knowledge on the EPI schedule resulted in three times more likely compliance to the childhood immunization schedule [4]. The knowledge on vaccines plays a pivotal role in the ability of the parent to comprehend the importance of adhering to the childhood immunization schedule. Those who had knowledge that vaccines could prevent disease and also limit illness to the child were more likely to adhere to the schedule and have a deeper understanding and increase in knowledge on childhood immunization [6]. As for the control group, the mean score at baseline was 61.7% and reduced further to 54.9% after one-month but increased to 85.1% three months post-intervention. The gap and difference in the knowledge on the under-five childhood immunization schedule can be explained as the control group had poor access to the knowledge or information on the immunization schedule. Those with lack of knowledge on vaccines were six times more likely to fail to comply with the schedule or have good knowledge [5].

Conclusion

We may acknowledge that although the difference between the intervention group and control group is visible, the marginal difference can be covered by introducing targeted health promotion materials to increase the level of knowledge among parents in any population [9]. This intervention shows that repetitive exposure to information results in not only increase in knowledge, but also permanent understanding as shown in the repetitive results of the intervention group [10].

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the participating nurseries in the districts and the cooperation of all the managers and education providers.

Abbreviations

DTAP:Diphteria, Tetanus, and Pertussis; Hib:Human influenza B ;Hep B:Hepatits B ; IPV: Inoculated Polio vaccine

Funding

This study was not funded by internal or external grant sources.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available by contacting the corresponding author at norafiah@uom.edu.my

Authors’ Contributions

MFR made contributions to the writing of the manuscript, data collection and analysis. NAMZ provided idea of the study design and the direction of the study process as well as the re-evaluation of the entire analysis. MHJ gave insight on the study design as well as the critical revisions of the research. MSL gave critical input on manuscript preparation, writing and re-evaluation of the research article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) ethics committee approved the study [UPM/TNCPI/RMC/1.4.18.2(JKEUPM)] and all participants consented by filling up the consent form and declaration prior to the involvement in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Global Report on Immunization for the 2015. 2016.

Awadh AI, Hassali MA, Al-lela Omer Qutaiba, et al. Does an educational intervention improve parents’ knowledge about immunization? Experience from Malaysia. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14: 254.

Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12–23 months in Ambo Woreda, Central Ethiopia. BMC public health. 2012;12(1):

Jani JV, De Schacht C, Jani IV,et al. Risk factors for incomplete vaccination and missed opportunity for immunization in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1): 1.

Negussie A, Kassahun W, Assegid S, et al. (2016). Factors associated with incomplete childhood immunization in Arbegona district, southern Ethiopia: a case–control study. BMC public health. 2016;16(1):1.

Tarrant M, Gregory D. Exploring childhood immunization uptake with First Nations mothers in north‐western Ontario, Canada. J advnurs. 2003;41(1): 63-72.

Guendelman S, Meade K, Benson M, et al. Improving asthma outcomes and self-management behaviors of inner-city children: a randomized trial of the Health Buddy interactive device and an asthma diary. Arch pediatradoles med. 2002; 156(2): 114-120.

Moray N, Inagaki T. Attention and complacency. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Sci. 2000; 1(4): 354-365.

Hennink-Kaminski H, Vaughn AE, Hales D, et al. Parent and child care provider partnerships: Protocol for the Healthy Me, Healthy We (HMHW) cluster randomized control trial. Contempclin trial. 2018;64: 49-57.

Cannell J, Jovic E, Rathjen A, et al. The efficacy of interactive, motion capture-based rehabilitation on functional outcomes in an inpatient stroke population: a randomized controlled trial. Clin rehab. 2018; 32(2): 191-200.

Received: July 02, 2018;

Accepted: July 25, 2018;

Published: July 27, 2018

To cite this article : Zulkefli NAM, Rusli MFB, Juni MH. Knowledge on Under-Five Childhood Immunization Schedule amongst Parents at Nurseries in Putrajaya and Cyberjaya in Malaysia. Japan Journal of Medicine. 2018: 1:6.

©Zulkefli NAM, et al. 2018.